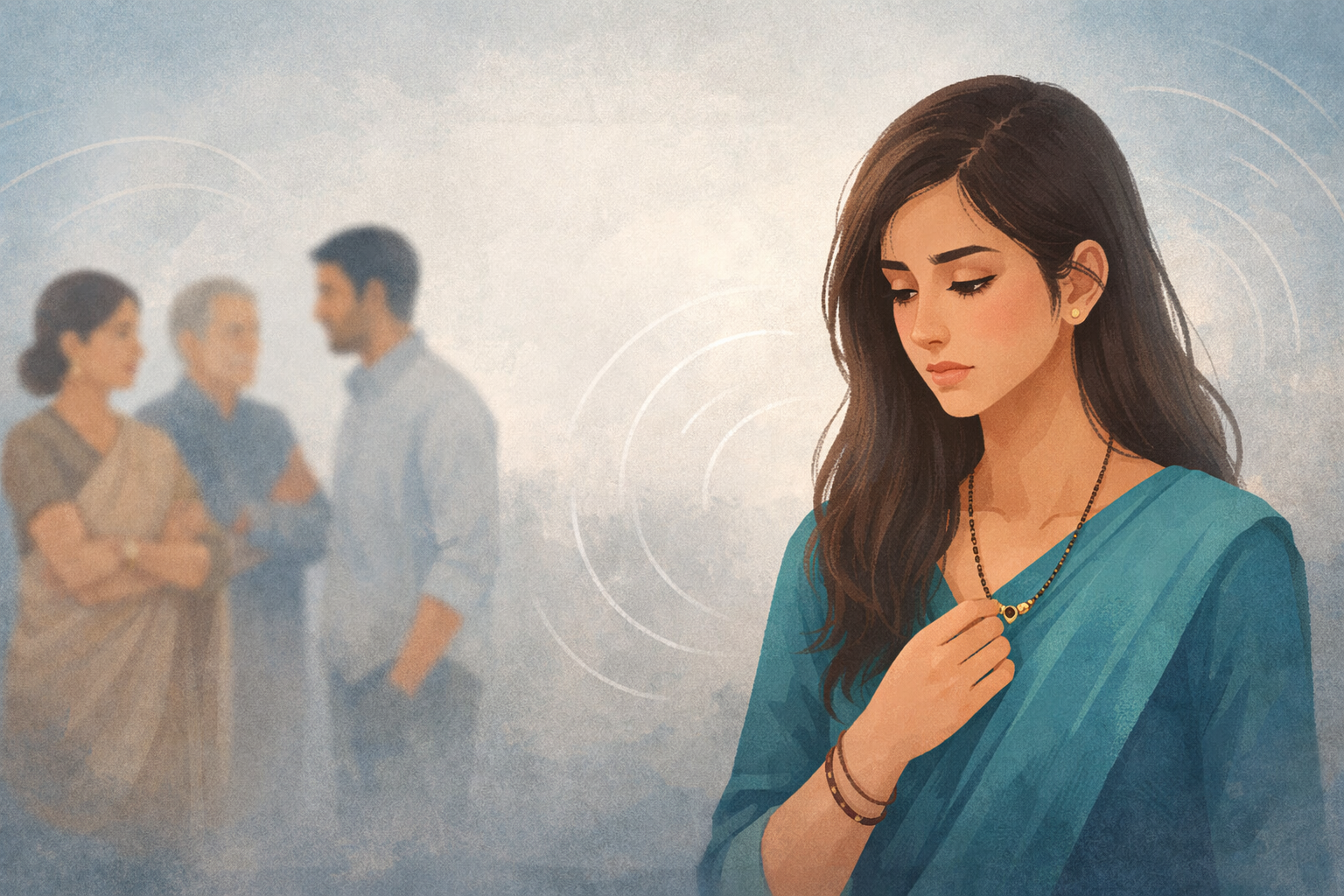

Between Tradition and Trauma: Understanding Toxic In-Laws in South Asian Marriages

In many South Asian marriages, family is not just part of the relationship, it is the relationship. In-laws often play a central role in daily life, decision-making, and emotional dynamics. While this closeness can offer support and belonging, it can also become a source of deep emotional distress when boundaries are crossed.

For many individuals, especially women, the pain caused by toxic in-law dynamics is often minimized, normalized, or dismissed in the name of tradition. This blog explores how cultural expectations intersect with emotional trauma, how to identify toxic behaviors, and how healing can begin without rejecting culture or self.

Cultural Context

Overview of South Asian Marriages

South Asian marriages are typically rooted in collectivist cultural values, where family unity, interdependence, and respect for elders are emphasized over individual autonomy. Research in cross-cultural psychology shows that in collectivist societies, personal boundaries are often less clearly defined, especially after marriage.

Marriage is frequently viewed as:

A union of families, not just individuals

A lifelong duty rather than an evolving relationship

A space where endurance is valued more than emotional expression

These values are not inherently harmful. However, problems arise when cultural norms are used to justify emotional control, neglect, or abuse.

The Role of In-Laws

In many South Asian households, in-laws may have authority over:

Household roles and responsibilities

Financial decisions

Reproductive choices

Career and mobility

Social interactions

Research on family dynamics shows that when families are overly involved in each other’s lives and personal boundaries are unclear, conflict and emotional distress are more likely particularly for daughters-in-law navigating new family hierarchies.

Identifying Toxic In-Laws

Characteristics of Toxic Behavior

Toxicity is not defined by disagreement or cultural difference alone. Psychological research defines toxic family behavior as repeated patterns that undermine emotional safety and autonomy.

Common examples include:

Chronic criticism or humiliation

Emotional manipulation disguised as “concern”

Guilt-tripping using sacrifice or duty

Triangulation (turning spouses against each other)

Controlling behavior over daily choices

Gaslighting or denial of lived experiences

The American Psychological Association emphasizes that emotional abuse does not require physical violence to cause harm.

Impact on the Spouse

Living in a toxic in-law environment can lead to:

Anxiety and depression

Chronic stress and burnout

Loss of self-confidence

Feelings of isolation or helplessness

Marital conflict and emotional withdrawal

Studies published in the Journal of Family Psychology show that prolonged family stress significantly affects mental health, relationship satisfaction, and even physical well-being.

The Intersection of Tradition and Trauma

Familial Pressure and Cultural Expectations

Many South Asian individuals struggle not only with harmful behavior but with the pressure to tolerate it.

Common internal conflicts include:

“If I speak up, I am disrespectful.”

“If I leave, I bring shame to my family.”

“Endurance proves character.”

Trauma research shows that when individuals are repeatedly told to suppress distress, the nervous system remains in a state of chronic stress, increasing the risk of trauma-related symptoms.

Trauma-Informed Perspectives

A trauma-informed lens recognizes that:

Harm can be unintentional yet deeply impactful

Cultural intent does not erase emotional injury

Survival strategies (silence, compliance) once served a purpose

The World Health Organization emphasizes that mental health care must account for social and cultural contexts, especially when family systems are involved.

Understanding toxic in-law dynamics through a trauma-informed perspective shifts the question from

“Why can’t you adjust?”

to

“What has this environment cost you emotionally?”

Navigating Relationships with Toxic In-Laws

Setting Boundaries

Boundaries are not acts of rebellion, they are tools for emotional safety. Research in family therapy shows that clear, consistent boundaries reduce long-term conflict.

Healthy boundaries may include:

Limiting certain topics of discussion

Defining personal space and privacy

Agreeing on decision-making roles within the marriage

Reducing exposure to repeated harm

Importantly, boundaries can exist with respect.

Seeking Support

Social support is one of the strongest predictors of resilience in family stress research. Support may come from:

Trusted friends or relatives

Support groups

Culturally sensitive therapy

The APA notes that therapy helps individuals differentiate between cultural values and harmful dynamics, allowing for clearer choices rather than reactive ones.

Healing and Moving Forward

Healing does not require cutting off family in all cases. It requires:

Validating your lived experience

Rebuilding self-trust

Redefining your role beyond imposed expectations

Creating emotional safety within or outside the family system

For many South Asian individuals, healing is not about choosing between family and self — but learning how to exist without losing either.

Conclusion

Navigating toxic in-law dynamics in South Asian marriages can feel isolating, especially when cultural expectations make it difficult to name emotional harm or seek help. If you find yourself feeling anxious, emotionally drained, or stuck between honoring family and protecting your well-being, you’re not alone and you don’t have to carry this on your own.

At Spiral Up Therapy, clinicians work with South Asian individuals, couples, and families using a culturally sensitive, trauma-informed approach. Therapy here focuses on helping you understand your experiences, set boundaries with compassion, and move toward healing without dismissing the cultural values that matter to you.

Support is not about choosing between family and self, it’s about learning how to care for both in healthier ways.